A Chilean School In Exile: An Experience 1979-1986

Hernando Fernandez-Canque

This is an account of the creation of the first Chilean school in exile in England. The article is a reflection of the situation that Chileans faced after their exile to England. In this article, I want to describe the experience of this school. I will outline the conditions that led to the creation of the first school in exile, the characteristics of the school, and its importance in the community of Chilean exiles in Sheffield and Rotherham. After this experience was shared, the example was replicated by Chile Democratico who created other schools in London. I write this article as the elected 'director’ of this school, but it was always a collective project of students, parents, and teachers.

Background

When Chilean exiles arrived in the UK, we encountered the challenge of settling in at the same time as facing the stress and difficulties of past experiences. As time passed, many of our children did not receive a full and coherent explanation of what had happened. The adults frequently referred to events, people, and experiences in relation to the repressive dictatorship period that the children were not familiar with. Departure from the homeland was traumatic, both for those who hoped to return and those who accepted that they would stay in exile. Former political activists with considerable experience of organising, debating and mobilising; now found themselves unable to communicate fluently in English, increasing isolation and frustrations in their new reality.

Adults (in exile). We were all affected by the brutal interruption of our personal history, in different degrees. The Chilean adults that arrived as exiles tended to concentrate on their present problems, unintentionally neglecting the difficulties presented to their children. For the adults, the priority was to overthrow the military dictatorship that would return their country to democracy and open the door to their safe return from exile. To this end, the priority activities were the political organising to strengthen the campaign against the unelected dictatorship. However disoriented or overwhelmed by new challenges, the adults were able to certain degree to understand what was happening to them. The children and preadolescents at that time were too young to understand the dramatic events in which their parents were actors and victims. In some cases, the children themselves were actors and victims. Many adults were too caught up in the effort to survive and unable to explain fully to their children the meaning of the events they were living through.

Children (in exile). Many children had shared the experiences of violence, insecurity, and loss with their family members. For the children, this happened in their formative age, before they had developed their own ideas and identity, and when they were still young enough to make sense of their experience. Some children reacted by avoiding conflict, feeling alienated from their community, or their parents. There were some features of the new society that parents showed little interest in, or positively rejected. In many cases, the past was of little interest for the adolescent, their identity was largely influenced by their experience in exile. This was different for their parents who may still have had cherished, and in many cases, hyper-idealized images fixed in the past.

Parents -children (in exile). The traumatic experience lived by the adults not only affected the exiles themselves, but also all those around him/her. Clearly exiles subjected to the effects of repression, oppression and torture, will face starting over in a weakened and vulnerable position. Exile is never an accomplishment of an aspiration, but rather a castigation. It is a brutal disruption of personal history; family, friends, work and social roles. People living in exile might also suffer from exclusion and may experience social, cultural and racial discrimination by the host country. The political repression directed against the parents, and the exile of the family, tends to distort the healthy development of social skills and inclusion for children. The plan for a Chilean school was a response to problems of exile indicated above, and because adults often prioritised their own concerns over problems confronted by their children.

The School

The school was a response to offset some of the negative characteristics of the new environment that children struggled with. We were working on the idea that a community-based initiative such as the Chilean school could help those in exile to settle in the host country as well as help prepare them for the possibility of an eventual return to their homeland.

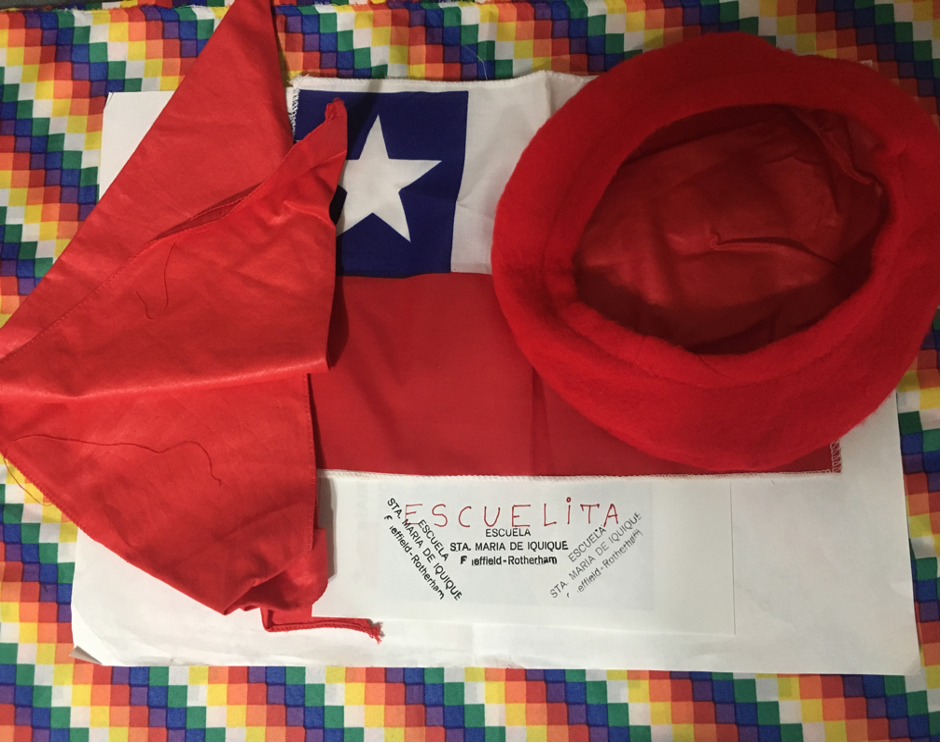

Invitation to the community for a school’s event

Origin. At the beginning of 1979 there was an attempt to create a school. This did not progress due to lack of community support, partly due to a lack of planning, insufficient preparation of the teachers, and a perception that there were partisan interests behind the initiative.

However, the idea of a school was still present and its necessity seemed more urgent as time passed. I contacted Magaly Matzer, a teacher with years of experience teaching children in the countryside in the south of Chile as a start to relaunching the plan. After Magaly agreed to join this project, we approached other teachers in the Chilean community to develop the work. After a few weeks of discussion with possible teachers, the final team was complete and consisted of 6 teachers: Magaly Matzer, Eliana Cornejo, Alejandro Cornejo, Cesar Viracca, Hilda Viracca and Hernando Fernandez-Canque. This team had the qualification and experience of teaching at all levels of education, in diverse environments and different systems of education. Hernando had also the experience of teaching in schools in prison camps in Chile (Tres Alamos and Ritoque).

School’s ceremonial beret and neckerchief

The team then concentrated on an arduous process of discussions to decide what we wanted to achieve. In this lengthy process all our knowledge of pedagogy, different educational systems, as well as diverse experiences, allowed us to generate shared perspectives of what we were aiming for. All of us had been exposed to new ideas circulating in Chile during the Unidad Popular government along with the stimulus of Paulo Freire’s ideas on education. The team formalised a set of objectives for this new school that would help explain to the parents what we hoped to achieve. At the end of this process, we agreed to work with the following objectives:

1.- Create a critical consciousness in the child

2.- Avoid absorption and alienation that easily distances children from the socio-cultural awareness leading to lose Chilean identity

3.- develop a spirit of collectivism

4.- Promote and channel cultural artistic skills

5.- Get to know Chile

6.- Achieve an adequate preparation in a possible perspective of a return

Once the objectives of the school were agreed, and the teaching staff were ready and with a preliminary program; we started the slow process of visiting each family to explain the project. At the beginning we managed to gain the commitment of a few parents and children. By the end of 1979 the school started with 12 students; after a few weeks other children joined. By the end of January 1981, the number of registered and attending students reached 45.

In its first phase, the school used premises at Sheffield Polytechnic. After a year we moved to a community centre provided by the city's Department of Education. The premises had a large hall, 2 rooms, and a kitchen. The classes were held on Saturdays in the afternoons from 2pm to 5pm. The afternoon was divided into 2 parts. The first part, from 2pm to 3:15 pm, included globalised teaching of Spanish, history, geography and elementary notions of economics. In these sessions, the students were divided into 4 levels. Their level was selected according to knowledge base whether acquired in Chile and/or in exile.

The second part from 3:30pm to 5pm was dedicated to workshops in agreement with the general objectives of the school. The aim was that the students apply a little of what was learned in the first timeslot. The session was designed for the students to gain an appreciation of manual work as well as the intellectual theory. These workshops included carpentry, painting, handicrafts, cooking, and folklore. The children elected 3 or 4 workshops per trimester. Up to 12 parents cooperated in this work over the duration of the school, working with the teachers to develop a stimulating and inclusive programme.

Occasionally we asked members of the community to give talks on topics such as the history of the trade unions, the peasant movement, coal mining, and other significant social organisations in Chile. Guest speakers were also welcomed to speak about their individual experiences growing up in diverse areas and communities of Chile both urban and rural. It was also intended to cover important current events happening in Chile. For example, in 1983, the children discussed a strike happening in Chile. They produced art work related to the topic and fundraised to send £50 to the workers in strike. The school also had extracurricular activities such camping trips and visits to museums.

All adult participants in the school provided their time and work as unpaid voluntary work. The teachers would meet for 4 hours over at least one session every week in order to prepare lessons and material for the Saturday class. There were additional meetings to plan for special events such as a celebration of Chilean National Independence Day on 18 September. There was also a regular ceremony to recognise the progress of the children. The initial funding was provided by the teaching staff from their own money to cover the absolute essential materials. At a later stage, parents and staff created fund raising events such as raffles, jumble sales, and donations. In 1982 Sheffield’s local authorities provided a grant of £250 to help the work of the school. The local education authorities of Sheffield also recognized the school as part of their project to support minority communities.

Apart from the subjects covered by the school, the teachers provided some support with difficulties that the children encountered in their regular school. Tuition in maths and English was provided as extra-curricular activities when required.

The age of the children/adolescents was in the range of 5 to 16 years old. By January 1981 we had 45 children registered from Sheffield, Rotherham, and surrounding areas, with an average attendance of 29 students per week.

The school was flexible enough to accommodate the interests and curiosity of the children. The environment was relaxed including children’s games and songs from Chile.

The Name of The School.

The first name for the original idea of the school was ‘Chile Volveremos’ (We Will Return to Chile). The school started without a name, at the end of the first year the teachers decided to dedicate 3 weeks to find a name. It was decided that the name be selected by the children. In the months prior to the naming of the school, the students had had a historical lesson about an important event of the Chile trade union struggle, in which a massacre of more than 3 thousand workers took place in the ‘Escuela Santa Maria de Iquique’. It would seem that this inspired the children to choose the name for our Saturday school “Escuela Santa Maria de Iquique”, often referred to by the affectionate name of ‘Escuelita’.

School’s Attendance Roster

The Chilean School was a labour intensive, and voluntarily set up and run within the community for the benefit of our second generation. It was a challenging project as all the volunteer teachers and helpers had their own struggles and sorrows in exile, but it was done with a tremendous spirit of solidarity and hope for the future. We all believed that education and shared history was an essential building block for our new lives and our work to support our comrades still living under the Pinochet dictatorship.

A Community of Children

The school was created to benefit the children. As a result, the whole Chilean community in exile was empowered. One of the fundamental benefits for the children was that the school created a community of the children and for the children. The students would meet every week, and share age-appropriate activities with their peers. A camaraderie was fostered where the children had a safe space for themselves. They could discuss ideas, problems, or worries that they experienced, as well as having the opportunity to be children together. Their contributions to the programme were solicited, respected, and welcomed. The children continued to meet and identify as a group after meeting through their involvement in the school. This was one of the major achievements of the ‘Escuelita’.

Final Comments

Some of us moved to other parts of the UK and got involved in new Chilean schools. After a few more years, some people returned to Chile. The memories of the Escuela Santa Maria de Iquique remained strong and positive, as an example of our unity and strength despite the many challenges of exile.

Dr Hernando Fernandez-Canque was born in Arica, Chile. He completed his first degree in telecommunication at the University of Chile in Santiago. In 1974, he was detained by the DINA secret police of the Chilean dictatorship, taken to the torture centre Jose Domingo Cañas and prison camps 4 Alamos, 3 Alamos and Ritoque. He was expelled from Chile with no due process at the end of 1975 to UK. Hernando continued his academic work with an honour’s degree in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (Glasgow University), Masters (UMIST, Manchester) and PhD (Sheffield University). He worked at Glasgow Caledonian University for 30 years as senior lecturer and Director of the Intelligent Technologies Research Centre (ITRC). He has over 100 research publications in International Journals, he has written book chapters and a text book “Analog Electronics Applications: Fundamentals of Design and Analysis”. he is currently a Visiting Professor at the university of Cluj-Napoca.

Hernando has taught at all levels and in various countries including teaching at schools created with fellow detainees in the prisoner camps of Tres Alamos and Ritoque. He is a fellow of the Higher Education Academic UK.

Hernando is a member of numerous solidarity campaigns. His Chile solidarity work includes : President of The Chile Society UMIST Manchester (1978/1979), President of Chilean Community Sheffield- Rotherham (1979-1986), Secretary of The Chile Society Sheffield University (1980-1985), Head teacher Chilean Saturday School Sheffield-Rotherham (1979-1986), Secretary of Chile Democratico West of Scotland (1986-2017), Head teacher of the Chilean School in Glasgow (1986-2000), Secretary Colectivo de Unidad Democratica(CUD) London (2017-present), Coordinator and treasurer Asamblea Chilena en Londres (2018-present), Secretary of Casa Chilena UK (2001-present), Chile50yearsUk-2023 Coordinator.