I worked as a volunteer in the UK Chile Solidarity Campaign (CSC) from September 1973 to late 1982, as editor of the campaign magazine, Chile Fights. I had no qualifications for this work, except the dubious benefit of a degree in English literature. I had no Spanish, no knowledge of Chile or Latin America, scant political education outside a couple of years in the feminist movement. All I knew about Chile was that in 1970 the then newly-elected Socialist president, Salvador Allende, had promised to give every child in the country a pair of shoes for Christmas. Straight out of a folk tale, I thought.

Some time later, I read about truck-drivers going on strike against the government and creating food shortages. Then, suddenly, one September morning, it was planes bombing the presidential palace, the President dead, a military junta taking over. That month, at the language school where I taught, I had a class full of Latin American students, all anxious to discuss the coup in Chile. I knew there was a left-wing Chilean student in the school, and I wanted him to come and talk. But he was desperately trying to organise protest against the new regime, so I offered to let him use the school duplicating machine to run off flyers for the first demonstration in London that weekend.

Long story short, I fell in love, with the student, and with the passion he brought to his cause. We are still married, 50 years later, and living in Chile. But that is the other end of the story.

Getting organised: Chile Lucha and the CSC

After that first march to Trafalgar Square, an ad hoc group of activists formed around this student, Raúl Sohr, and we called ourselves Chile Lucha (Chile fights). Within a few months we became an organising centre for a dozen or so British people, several of whom had spent time in Chile during Popular Unity and were highly motivated to campaign against the military junta and for its victims.

These “returnees” included Mike Gatehouse, who became general secretary of the Chile Solidarity Campaign (CSC), and Wendy Tyndale, who formed and ran the Chile Committee for Human Rights (CCHR). Both were independent activists, but we all worked closely together. Mike and Wendy were both (badly) paid full-time workers for the two organisations; almost everyone else was a part-time volunteer. Gordon Hutchison was another reluctant returnee from Chile, who helped set up and run the Joint Working Group for Refugees, a few months later, receiving and resettling Chilean exiles.

The CSC was an ad hoc alliance of the Labour party and the British Communist party, with the support of the main trade unions, and the small Trotskyist party, IMG. The CSC’s aim in the early months was to try to isolate the new Chilean regime, which the Conservative government of the day had swiftly recognised. The Tories had no sympathy with Allende’s ousted Popular Unity government, an alliance of Socialists and Communists and other small left-wing parties, who had been attempting a “peaceful road to socialism”.

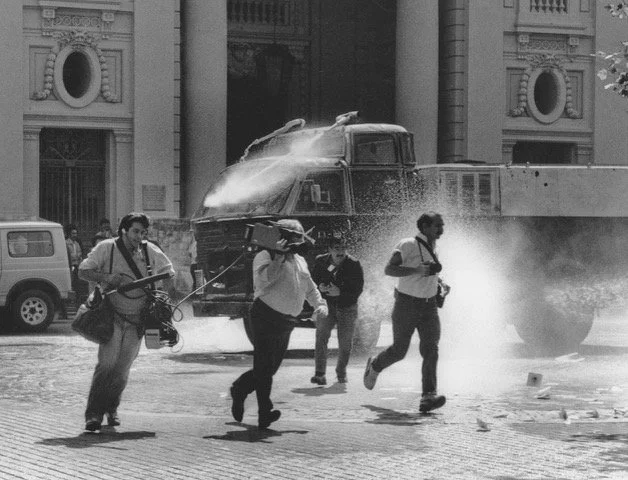

The images of the coup - the bombing of the presidential palace, Allende’s violent death, the use of the biggest football stadium in Santiago as a prison and torture centre, - were disturbing. The regime had immediately suspended all political parties, left and right, banned the trade unions, and detained thousands of supporters of the previous government. But the Tories could assume, if they were worried about it, and as their Chilean counterparts assured them, that these undemocratic measures were necessary to restore order and take control of the country, and were just for a few months, a year or two at most, and then there would be elections and a return to democracy.

The Chilean left, too, hoped at first that the military would not stay long. So the task of the international solidarity campaigns was to speed their departure by making business and political activity as hard as possible, to discourage foreign investment, trade and aid, and diplomatic activities. But it was soon clear that Pinochet and the junta were there to stay, and were strengthening their control through continuing political and physical repression. The campaign continued, aiming to deny them legitimacy and to publicise the killing and disappearance and torture of their opponents. But it also had to focus on trying to help the victims, and on campaigning for visas for refugees, many of them prisoners who were forced to choose between prison and exile.

The UK response

Surprisingly, given the general ignorance and lack of interest in Latin America at the time, the cause of Chile caught on in the British left. Partly it was a very clear story: a democratically elected government seeking peaceful change had been overthrown by a military coup. And surprisingly strong emotional support came from old memories in Britain of the Spanish civil war. I remember marching in a Chile demo beside the banner of a group of veterans who had fought in Spain in the 1930s. In 1974, General Franco was still alive, and good leftists and trade unionists still refused to take holidays in Spain.

In March (1974), political conditions in the UK changed for the better for the Chile campaign, when the Conservative government was thrown out and the Labour party took office. There were at least a dozen friendly Labour MPs who would support actions against the Pinochet regime – for example, successfully lobbying against renegotiating the terms for Chilean international debt.

Dame Judith Hart, MP, who was minister for overseas development, re-purposed aid funds earmarked for the Chilean state into scholarships for Chilean refugees. One Labour MP, Eric Heffer, resigned as a junior minister in protest when his government decided to return two Chilean-owned submarines then in a British shipyard for repairs. The trade unions played a key role with actions at grass roots levels, like boycotting work on the four Hawker Hunter plane engines in Scotland; and their leaders supported the campaigns.

Uniting Popular Unity

Immediately after the coup, a risk to a successful campaign was the disunity and infighting within the Chilean left, which had undermined the Popular Unity government and now threatened the solidarity movement.

The Chilean Communists and part of the Socialist party had been the promoters of the “peaceful road to socialism”, and they accused their own allies, the more radical wing of the Socialists and small parties like the MAPU and Christian Left, of “infantile leftism”, of organising factory and farm takeovers, for example, and so provoking the coup. These groups responded that their “reformist” opponents had failed to organise to prevent it.

After the coup those divisions split the solidarity movements in some countries. In France and Italy, for example, Chile committees sprang up in alignment with specific Chilean parties, whose leaders controlled them. But in Britain the handful of Chilean leftists who now found themselves in exile reached a key political agreement: to keep their disagreements out of the campaign. Neither side would blame the other, at least in public, and there would be one united solidarity movement. Further, the campaign would be headed and run by British people, responding to British political concerns and norms, and using familiar language. The Chilean leaders would stay in the background,

Incidentally, within British political circles, there were also apparently fears of splits, that Labour Party and Labour-affiliated trade union leaders might opt to form their own solidarity campaign, without the Communists. But this, too, was avoided.

A national network and “Chile Fights”

A large part of our work as volunteers was to go and talk at meetings organised by trade unions and student unions and local political party branches, explain what was happening in Chile, and persuade them to support the CSC. This meant financially, by affiliating and paying dues, and politically, by lobbying their own leaders and local MPs to support specific actions, such as giving visas or not buying Chilean-made goods.

In many towns, local activists formed local Chile committees which organised events and meetings. At the height of the campaign, around 1974-1977, this was a strong network of some 30 committees, and we held regular meetings around the UK to coordinate amongst ourselves.

We needed to spread the news of what different groups were doing, to share ideas and tactics, and also to provide news about what was happening in Chile. And before the existence of social media, the only way to get the news out was to publish it yourselves. On paper.

Very early on, we in the Chile Lucha group had decided to start a magazine. The first issue, - called Chile Lucha – appeared at the end of September 1973. It was a sober, professional newsletter-style format, four pages in black and white, few graphics, and the print run was maybe 400 copies.

The second issue went to another extreme. The front cover was a stark black star on a white background, with the words “chile lucha” and “solidaridad” (sic). The print run was 10,000. When we tried to sell or even give it away, people would smile apologetically and say they didn’t speak Spanish. The third issue swiftly became Chile Fights.

Chile Fights became the official campaign magazine, and we at Chile Lucha worked most directly with Mike Gatehouse. For some time, he also ran a separate editorial project with its own team, the “Chile Monitor”, an occasional, duplicated newsletter. Its task was analysis, not propaganda; it set out to show, for example, how the military’s free market policies were directly underpinned by the repression of the social and political movements.

Where did we get news from? In those days, long before the arrival of 24-hour news channels, there was far less international news in the general media. There was very occasional reporting, Richard Gott or Christopher Roper in The Guardian, Hugh O’Shaughnessy in the Financial Times. We shared news from other solidarity organisations, like NACLA and Nich in the US, and from Germany’s Chile Nachrichtung. We would very occasionally see copies of Chile’s main newspaper, El Mercurio, with its version of events. We sometimes received direct accounts from Chile, in fuzzy carbon-copies of letters sent out by clandestine activists, mostly reporting raids on poor neighbourhoods, and the detentions and disappearances of militants. Amnesty International workers would have similar reports to share. There was little or no news of resistance.

Campaign coordination

As magazine editor I took part in the regular CSC executive committee meetings, where the different areas of the campaign reported and coordinated. The trade union affiliates were represented by officials from the two biggest unions, TGWU and AUEW, and from the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). There was also a cultural committee which organised fund-raising concerts and other events.

The Joint Working Group for Refugees (JWG) and the Chile Human Rights Campaign (CCHR), both independent organisations, sent their observers, who brought their concerns and campaigning issues. They in turn were in touch with, for example, Amnesty International, and the World University Service, (WUS), who worked on a much broader scale. It was a remarkably flexible and effective network of organisations.

Sometimes the campaigns were around specific issues, like trying to stop arms sales to the Chilean junta, under Margaret Thatcher’s government (1979). That would mean getting the CSC’s local Labour Party and trade union affiliates to lobby their MPs to raise or support questions in Parliament. Sometimes they were publicity campaigns, like calling for consumers to boycott Chilean fruit and shoes and wine. Activists would turn out to hand leaflets denouncing the junta to puzzled shoppers at Marks and Spencer.

The magazine would run occasional reports on the banned trade unions trying to organise in Chile, and call for CSC union affiliates to make contact with Chilean counterparts – we could provide contacts. Or it would call for help for soup kitchens for Chilean school children, or for support for political prisoners. There was a constant effort to build connections between UK and Chilean organisations. This, remember, in the days before internet: communications were by letter, which could take weeks to arrive. Long-distance phone calls were prohibitively expensive.

The production of the magazine was laborious. The articles were written on manual typewriters, or even handwritten; for any substantial corrections, the pages were literally cut up and pasted onto a clean sheet. This copy was then typeset (re-typed in columns on an electric typewriter), to produce clean, printable pages. These were cut up and pasted onto a design sheet. Fiona Macintosh, the designer, would struggle with the earnest writers and editor (me), to cut down the word count to allow space for graphics. Headlines in larger, or even different type faces had to be transferred from sheets of Letraset (thankfully, a lost technology).

The final sheets would be packed up and sent by train to Nottingham, to the friendly Russell Press, to be printed, folded, stapled and sent back to the CSC office in Seven Sisters Road, to be packaged up and taken to the post office to send out to local committees and affiliates to distribute and sell – or even read. What child of the internet can begin to imagine spending so much time, so much physical effort on publishing?

Moving out to Latin America

From the first issues to the last, in 1983, the magazine content gradually broadened to include news of other Latin American countries. With the 1976 coup in Argentina, the Chile Lucha group and others helped form an Argentine support group, which plugged into the Chile network. I was also working by then at Latin American Newsletters (LAN), a specialist publication, and had access to far more news sources about the region. In 1979 came the revolution in Nicaragua, and Chile Fights covered events in Central America, and US policy in the region under the Reagan government. The 1982 Falklands/Malvinas conflict was another big issue in the magazine, relating as it did directly to UK relations and policies towards Latin America.

But from 1979 onwards, the Chile campaign was winding down. A number of CSC activists from different parts of the UK went off as volunteers to support the Sandinista revolution, and also to projects in Bolivia, Peru and other parts of South America. Others went to work, often in the field, in aid agencies like Christian Aid, War on Want and Oxfam. These “Chile veterans” brought a strong political and social, and practical, focus to their work. It’s probably fair to say they marked these agencies for at least a generation.

We went on producing Chile Fights until (I think) 1983. Today the internet and all its platforms have transformed our access to news, and the distribution of all kinds of communications. I can’t imagine anyone would dream of producing a physical, printed publication. But working in the Chile campaign and learning journalism and politics on the job was an extraordinary experience, one that literally changed my life, and the lives of all of us who met and worked together and formed lifelong friendships as a result of those few, intense years.

Imogen Mark, Santiago, October 2023.